This is a summary of a research paper for which a gated link as well as a pre-publication copy are available.

How would you rate your neighborhood? There’s any number of services that provide metrics about a given community: home values, crime rates, walkability, information about local schools and other services – but some of the most important things about a community are hard to put a number on. Social scientists have long argued for the importance of ‘social capital’ – the degree to which members of a community trust each other and are able to work together – as a way to measure the health of a community. But it has always been difficult or cost-prohibitive to measure this at the community level. My colleague Ben Newman and I have shown that little-used census administrative data can do exactly that.

What’s Taiwan times two?

It’s an old problem in social science: while it’s easy to ask people for subjective opinions about, say, their favorite coffee shop, it’s much harder to come up with a number you can point to and say: this one is 5 points better, or half as good. It’s just not the way that people tend to think.

For a potentially more consequential example, what about democracy as a form of government? Scholars of politics have a pretty good sense about which countries in the world have more democratic systems of government than others, but it can be difficult to get a handle on quantitative measures (though some do exist). How do you rate Liechtenstein on a scale from Iceland to North Korea (perhaps not as high as you might think)? Some might argue that putting a number to demcracy doesn’t even make sense. It’s a matter of apples and oranges. All we can say is that they are different.

But failing to measure something that’s genuinely important has consequences. The better social scientists can measure these kinds of intangible qualities, the better we all can understand what factors make them more likely. It also means people making public policy can do a better job of tracking them and targeting interventions with these things in mind.

Social capital

We know that some communities just seem to work better and have neighbors that look out for each other. Some neighborhoods have so many things going against them that the case is obvious that they are worse off than others, but it can sometime be difficult to measure this sense with the data that tends to get collected. Robert Putnam, best know for his book Bowling Alone, uses the term ‘social capital’ for this quality of how well a community works together. He was first to argue that social capital forms the bedrock of what makes communities successful. More specifically, social capital exists where there is a set of interconnected social networks among neighborhoods, when neighbors tend to believe they can trust each other, and if one person pitches in to help out another today, they’ll be helped out in turn sometime down the road. Communities with relatively high levels of social capital aren’t necessarily wealthier, though concentrated poverty and associated problems obviously make this ideal harder to reach.

The census has already done the work

Social capital is important, but measuring it can be extraordinarily expensive.

Putnam and others working in the field have measured social capital with surveys, but it’s rare that any one survey will go in enough depth to get an accurate estimate for small communities, or enough breadth to measure many communities, to make comparison between them in terms of social capital useful. But there is at least one organization in the US that has the budget to survey practically every person in the country. And while the framers of the Constitution didn’t have the well-being of American communities in mind when they mandated the decennial census, in the course of their ordinary work modern census takers leave a trail behind them that lets us do precisely that.

Because the US Census Bureau has such a massive job to do every ten years, they do a lot of planning. It’s particularly important for them to have a good idea of how hard it will be to track people down. The law says they have to count everyone. If they can count on you to return your census form yourself, that’s another door they don’t have to hire someone to knock on. They keep track of who on your block turned in their form last time, and they have a count of that for pretty much every neighborhood in the country.

This specific behavior – turning in a census form early – actually tells us a lot about a person, and a community, beyond how easy it is to carry out the census. If you think about it, responding to any survey is really a small donation of your time. There’s a lot of research showing that people who are more likely to volunteer for surveys are also more likely to volunteer their time for community service or to turn out to vote. In part this may be because they have fewer things competing for their time and attention. But maybe they are also more likely to give their time because they’re the kind of person who expects someone else would do the same for them. Maybe by asking a small favor of someone from every household in the country, the census bureau is engaging in an enormous social experiment. In effect, they’re measuring how much each person believes they can count on others to repay a favor.

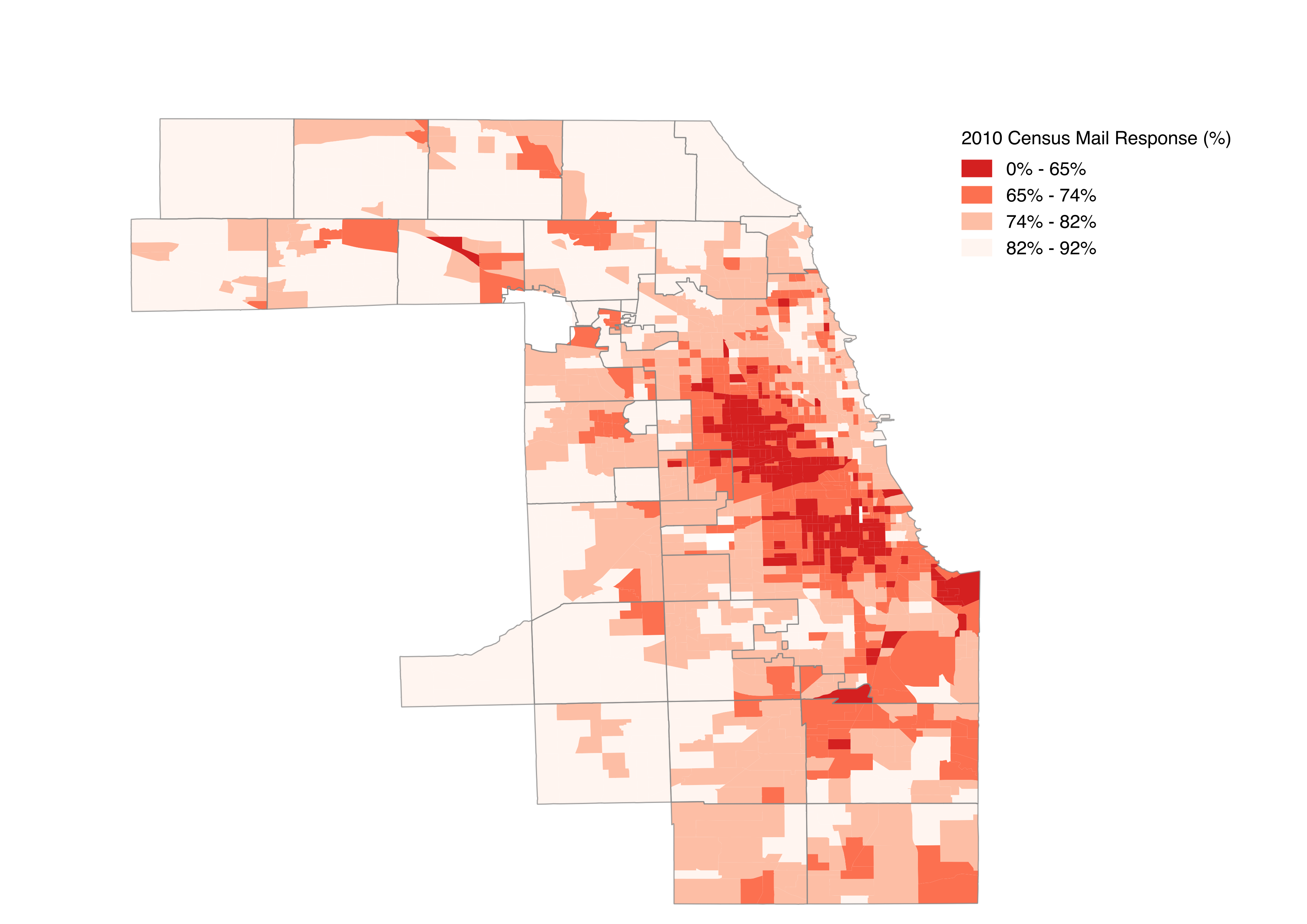

Census response rates in Chicago

Census response rates in Chicago

Our analysis seems to bear this out. We compared census response rates to a variety of surveys, including deep-dive polls that pulled from large samples of individual communities around the country, as well as a large-scale survey of neighborhoods throughout Chicago. We consistently found that census response rates were high in communities where people reported being more likely to interact with their neighbors, cooperate with their neighbors to solve common problems and believe that they could have a positive imapct in bettering their community. Even controlling for things we thought could be driving this result, things like income, family structure, racial and ethnic makup or age distribution, we found that communities with higher census response rates were more socially and civically engaged. In short, in carrying out its day-to-day work, the Census may unwittingly be mapping how likely neighbors are to get along on every block in the country.