What follows is a summary of the findings of a research paper for which a gated link as well as a pre-publication copy are available.

Just a week away from the 2012 Presidential election, the polls showed a tight race between the two major party nominees, but both campaigns were forced to halt operations at the last minute due to a massive storm on the horizon. Hurricane Sandy would go on to cause over $50 billion in damage, making it among the most desructive natural disasters in US history. A disaster of this magnitude so close to a Presidential election was unprecedented. No one could be sure what impact it would have.

After the election, my colleague Yamil Velez and I assembled data on election results and federal disaster assessments to figure out just how big a difference it made. We estimated that the effect was actually quite large: President Obama received a roughly four percentage point bump in his share of the vote in areas affected by the storm. And while it’s unlikey that the hurricane tipped the scales of the election overall, it did probably influence the electoral college results in some states.

Shark attacks, college football and the American voter

While it’s generally believed that last-minute events can have a big impact on elections, it was hard to know exactly what the effect of this particular storm might be.

There’s a well-known, if dubious, tradition of ‘October surprises’ in American Presidential elections. Campaigns have often been forced to deal with late-breaking scandal, knowing that even a momentary swing in voter sentiment could make a big difference in the final days before polls open. In the 2016 election, for example, some argued this was precisely the impact of statements by then-FBI Director James Comey regarding the FBIs continued investigation into Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton’s private email server. Whether intentional or not on the part of Director Comey, the statement came out mere days from the election, with many in the Clinton camp concerned it gave an edge to Trump.

But natural disasters may be different. Some argue a disaster can tell voters more about a candidate than just their ability to handle a PR emergency. If the campaign process is an opportunity to learn as much as possible about a candidate’s qualifications before votes are cast, a major storm could be seen as a way to show the true character of the current president’s leadership. In a recent book, political scientists Christopher Achen and Larry Bartels refer to this as the ‘folk theory’ of democracy: voters know pretty much what they want from a leader, and they can do a pretty good job of sizing up candidates to see who will best give these voters what they want. They just need enough information to make a decision. In that light, a President who acts decisively in the face of tragedy could see a boost in support.

But Achen and Bartels are skeptical. Leaders often do suffer electoral consequences when things go wrong on their watch, but they also tend to get blamed for things beyond their control. Presidents lose votes when the economy tanks and school boards take a hit for failing test scores. A leader might have some amount of control of these things, but other things are harder to tie back to the person in charge. For example, there’s evidence that incumbent members of congress are more likely to win their seat when their local college football team is doing well. Drought, flooding, even a rough spate of shark attacks at public beaches has been linked to incumbents taking losses at the polls. In other words, while a president could get rewarded for acting decisively in a time of crisis, they may just as easily take blame from voters for events far above their pay grade.

In the specific case of Sandy, polls after the fact showed an overwhelmingly positive appraisal of the relief effort, from President Obama to the governors of New York and New Jersey and the New York City mayor. Polls did seem to register an uptick in support of Obama shortly after, but pundits still disagreed on exactly what impact the storm might have had on the election – if it had any at all.

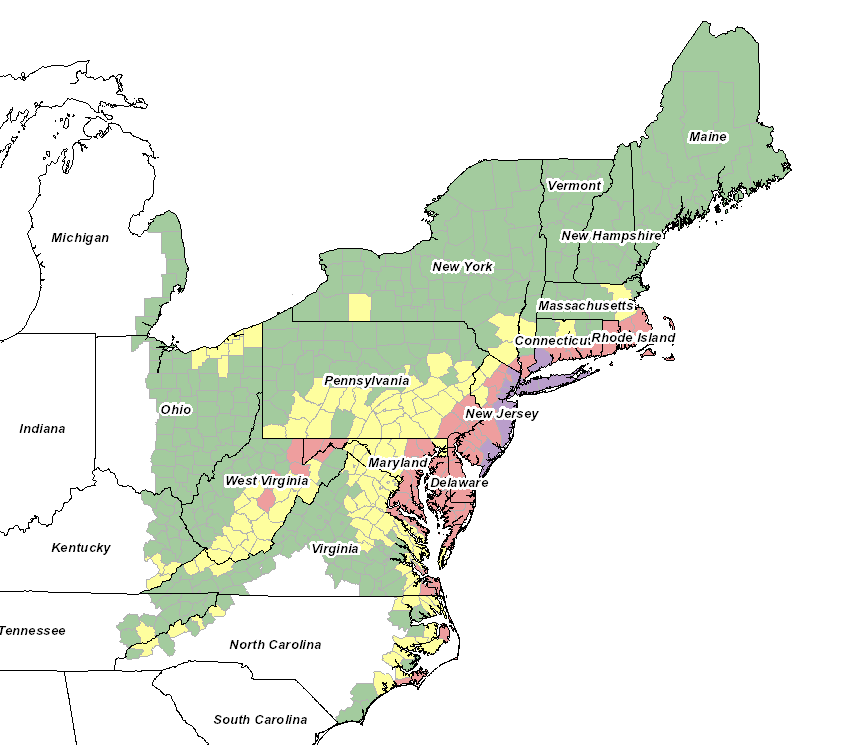

FEMA map of states affected by Hurricane Sandy

Measuring Sandy’s impact

In order to estimate the impact of Hurricane Sandy on the election, we started with a basic assumption: storms hit some places rather than others more or less by random. Obviously coastal areas are more likely to be damaged than those far inland, but precisely where on the coast is notoriously difficult to predict, even with state-of-the art weather models. From a statistical point of view, this randomness was useful because it meant we could treat this as a natural experiment. Think of it like this: imagine two towns are exactly the same but only one is hit by the storm, entirely at random. Both towns go to vote. If the process was truly random and the towns were the same, we could assume that any difference in the outcome is because of the storm. There may even be small differences between the towns, purely by chance. This complicates things a bit, but with data from enough towns we can get a pretty good estimate.

Of course, some areas really were more likely to be hit than others. We accounted for this by using a matching algorithm that took counties that were affected by the storm and found another county in the US that was nearly identical but was missed. We matched counties along as many metrics as we had (income, population demographics, recent election results, among others) to make the most fair comparison possible and measured the difference in the election outcomes.

Taking into account all the areas that were affected, we found that the average impact of the storm was about four percentage points in the vote share between the two major party candidates, with a margin of error of two percentage points. Though the estimated impact was fairly large, we recognized the areas that took the brunt of the storm – Connecticut, New York and New Jersey – were never likely to go for Romney under any conditions. The storm was almost certainly not decisive in handing the election to President Obama. Nevertheless, it may genuinely have had an impact on the electoral college vote count.

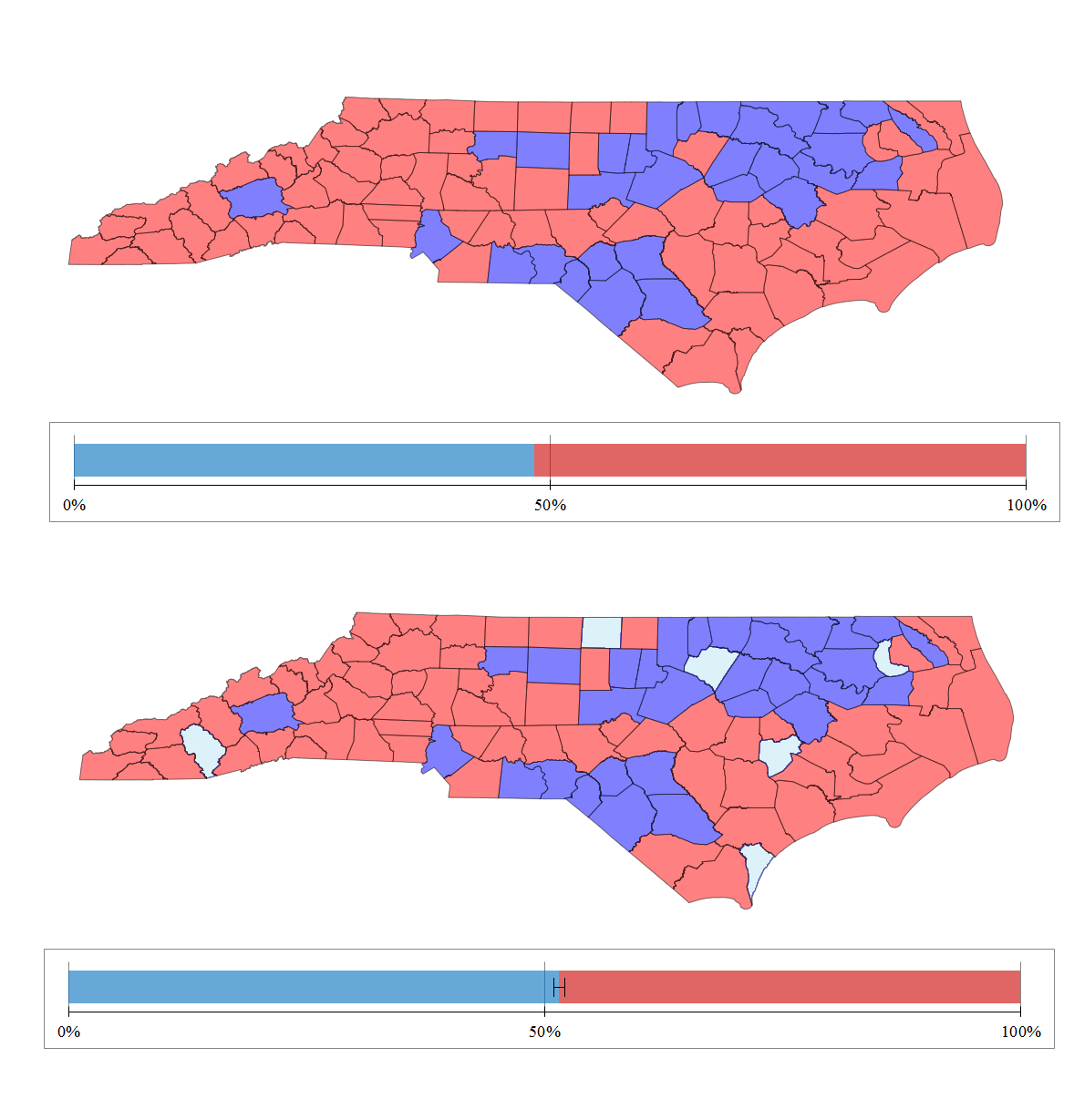

Above: The North Carolina counties Obama won in blue, and his overall state-wide vote share.

Below: We estimate the light blue counties would have flipped for Obama, along with North Carolina overall, had the storm covered the state.

Though some weather models predicted North Carolina was in the hurricane’s path, it was mostly spared and Romney won by a narrow margin. We estimated that if all of the state’s counties had been hit by some severe weather during that period the impact would have been enough to flip North Carolina for Obama.

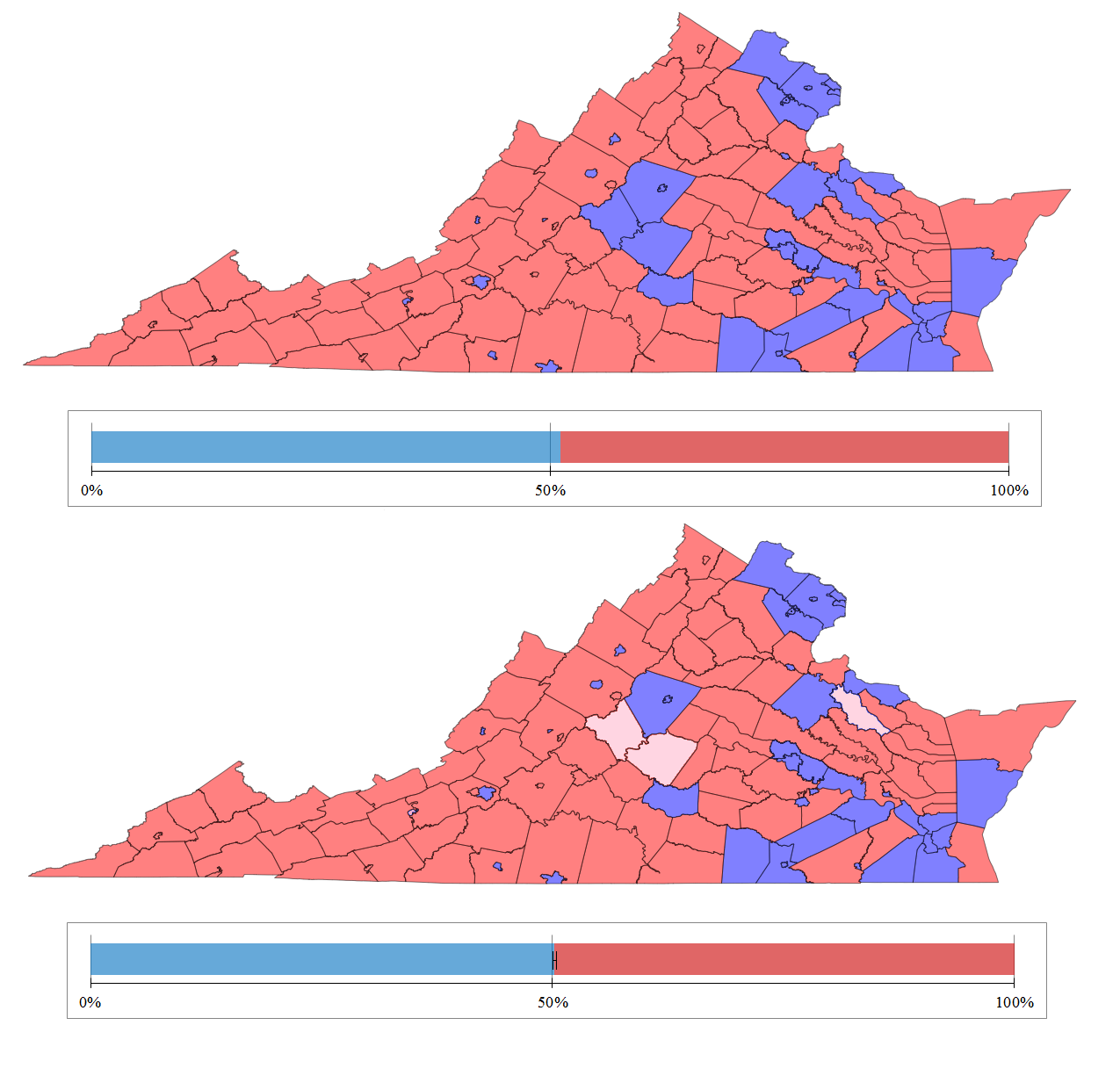

In the case of Virginia, another key swing state, there was significantly greater damage. Obama won the state. By our estimate, if the storm had missed Virginia entirely Romney probably would have won the state instead.